[Note: Best viewed on a nice big monitor as there are lots of photos, which may take a while to load. The full photoset is also on Flickr.]

Day One

I first heard about Dave Yates’ course when I read Bella Bathurst’s The Bicycle Book, published in 2011. The first chapter of her excellent book details how she built her bike, and it got me very intrigued. Although I’ve always lived with off-the-peg bikes, something that was very personal to me sounded wonderful. I’d guess that Bathurst must have attended his course in either 2009 or 2010. Dave says that he started the courses in earnest when he moved to his Lincolnshire home in 2005.

This year he’s been doing about 6 courses – each with two people. Next year there may be fewer, and who knows beyond that.

Bathurst noted in her book that his courses tend to be booked up well in advance. I booked a course by enquiring back in early 2015. While someone dropping out of a 2015 course meant there was some late availability then, I wasn’t able to take it. So, when in September 2015 an email dropped into my inbox giving the 2016 dates, I knew I had to move fast. To book a spot, I had to make a deposit pronto. That meant dashing out to the bank – from a work conference no less – since my mobile banking app wasn’t working at the time.

And so, some ten months later, I found myself in Lincolnshire, checking into a nearby B&B, ready to do the course.

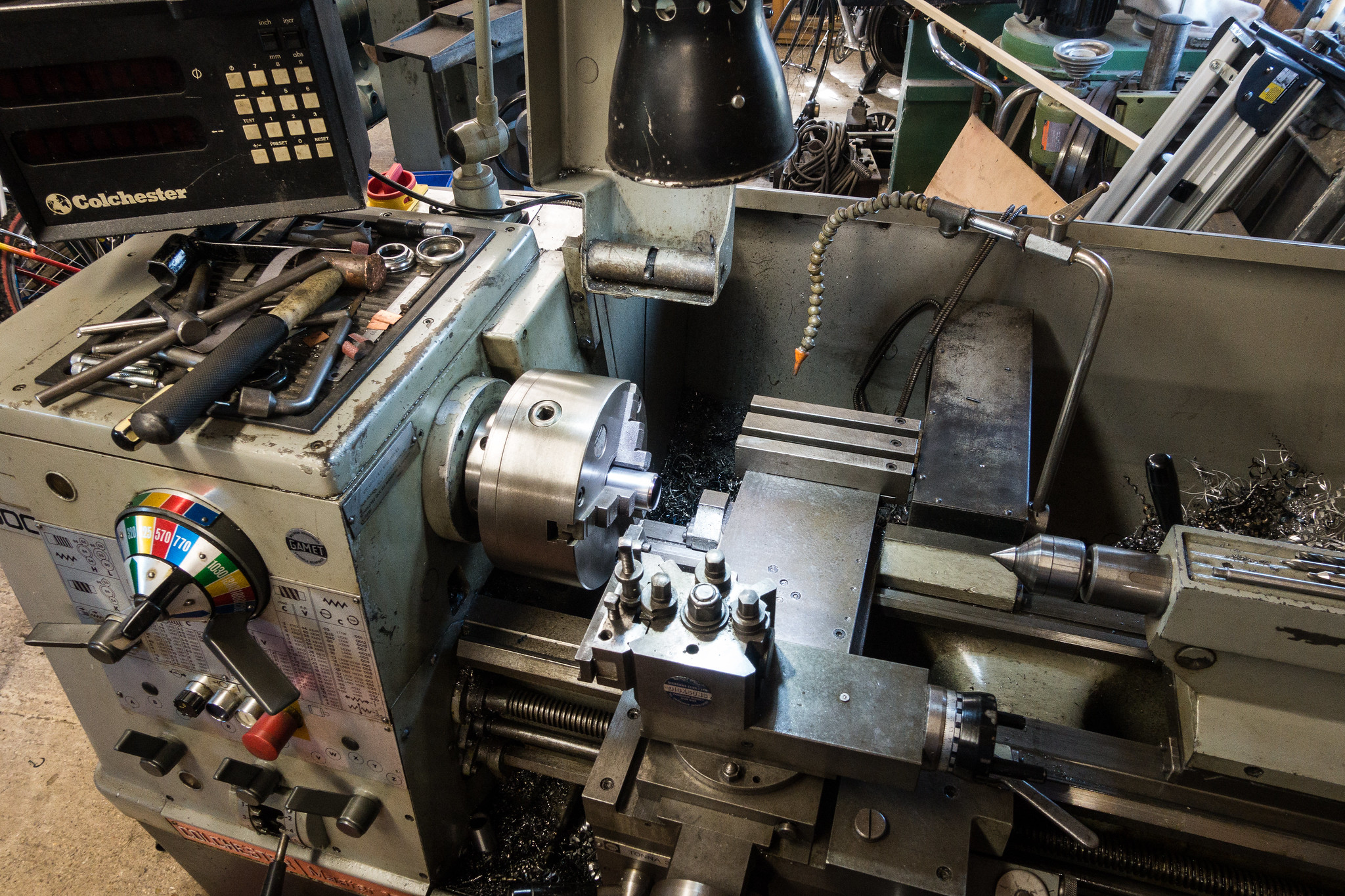

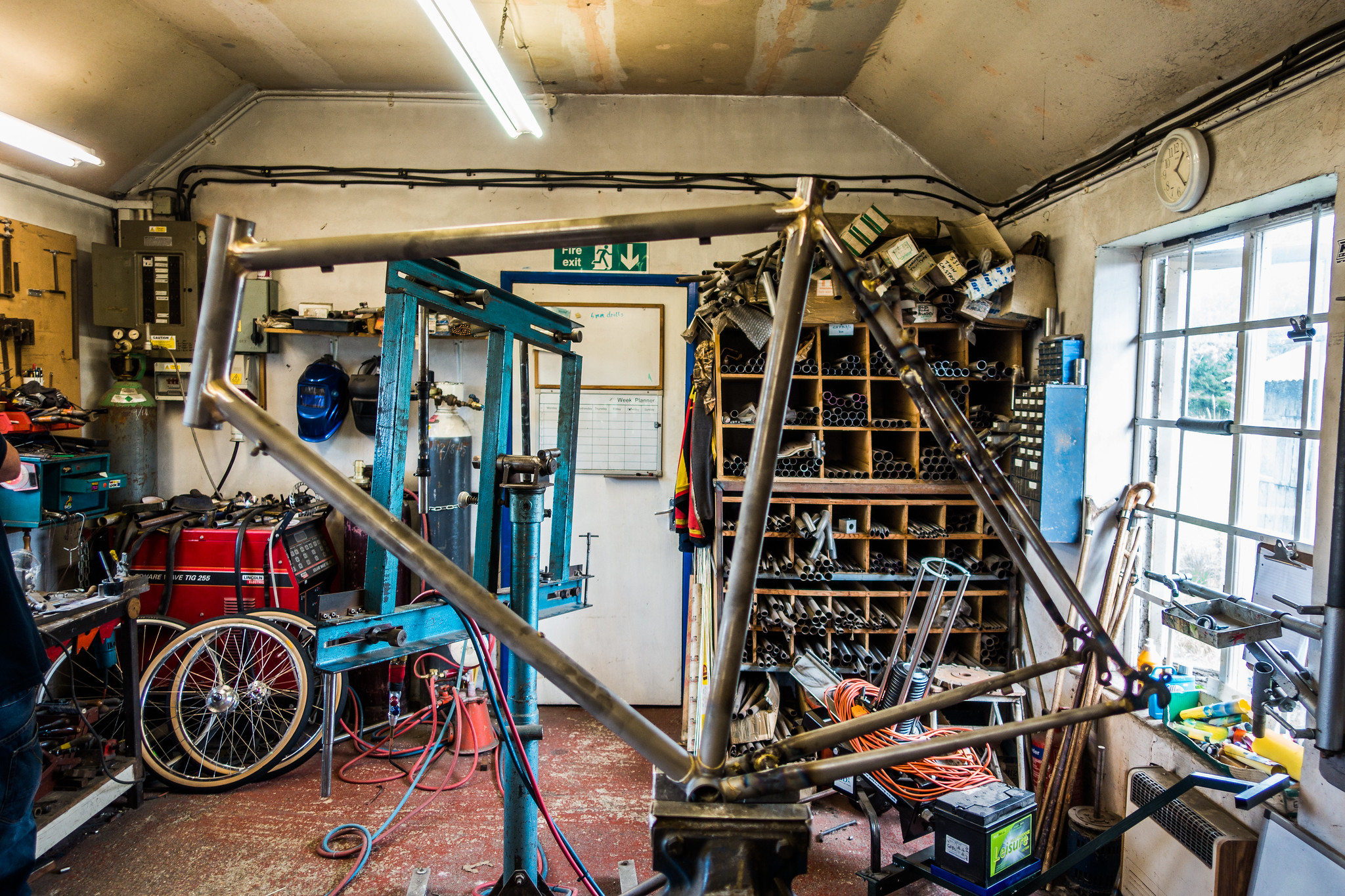

Dave’s property is quite large and he has a separate entrance for his bike business. Today he still builds frames, although he’s fairly choosy about what work he takes on. The workshop comprises of two rooms – one with several workbenches where most of the filing and brazing takes place – while a second room houses some large industrial machines that Dave has collected from various sources over the years. Notably they include a massive lathe and a large mill.

Now my metalworking skills are pretty primitive – that is to say – non-existent. Although there was metalwork at my school, if you were academically strong you didn’t really do it. In all my years of education, I spent more time doing pottery than either metalwork or woodwork. Indeed, I had one precisely one term of the former (I made a bottle opener) and I never set foot in the woodworking shop at all.

When signing up for the course, we were assured that lack of metalwork skills wouldn’t be a problem, although my fellow student did seem to have done a bit more than me.

Introductions made, and tea brewed, the first morning was largely discussions about what we wanted to build, how some of the kit worked. Not least was an introduction to the oxy acetylene torch. We also chose the various components of our frame.

There was, however, have a major distraction. Dave’s workshop is adjacent to RAF Coningsby, which is home to both Eurofighter Typhoons and the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight.

When I’d arrived at my B&B on Sunday, the first thing Eve, my landlady told me, was that the Lancaster was flying today. It was the first time it had flown since April 2015, after a fire had damaged it. Now the various repairs had been carried out on what is currently the only flying Lancaster Bomber in the UK (there’s another in Canada), and it was performing that day!

I’d headed out for a late afternoon/early evening bike ride, and ended up getting enormously side-tracked when I’d realised that the plane was going up again. The Rolls-Royce Merlin engines make a wonderful noise when they pass by.

Once in the air, the plane had repeatedly looped around the base, delighting plane spotters who’d gathered at several viewing points near the end of the runway. Moreover, the pilot deliberately passed by fairly low – as little as 250 feet – delighting all.

Now today, and it was clear the plane was flying again, it’s regular manoeuvres taking it low over Dave’s workshop meaning we regularly stepped out to look on in awe.

What’s more, it was later accompanied by a Spitfire and a Hurricane, with the three flying in formation. A wonderful sight.

The reason for all of this activity is that the pilots have to get their licences to perform at air shows, so that means repeated manoeuvres as though they were at an air show. And there are several pilots. For us, it meant a free display. And if it wasn’t the Lancaster interrupting us, it was a Typhoon, heading off towards Wales to fly low through the valleys. The way they can ascend vertically is remarkable and makes a terrific sound. If you’re even up in that particular piece of Lincolnshire, bring a camera – sadly I’d not though to pack my DSL and long lens.

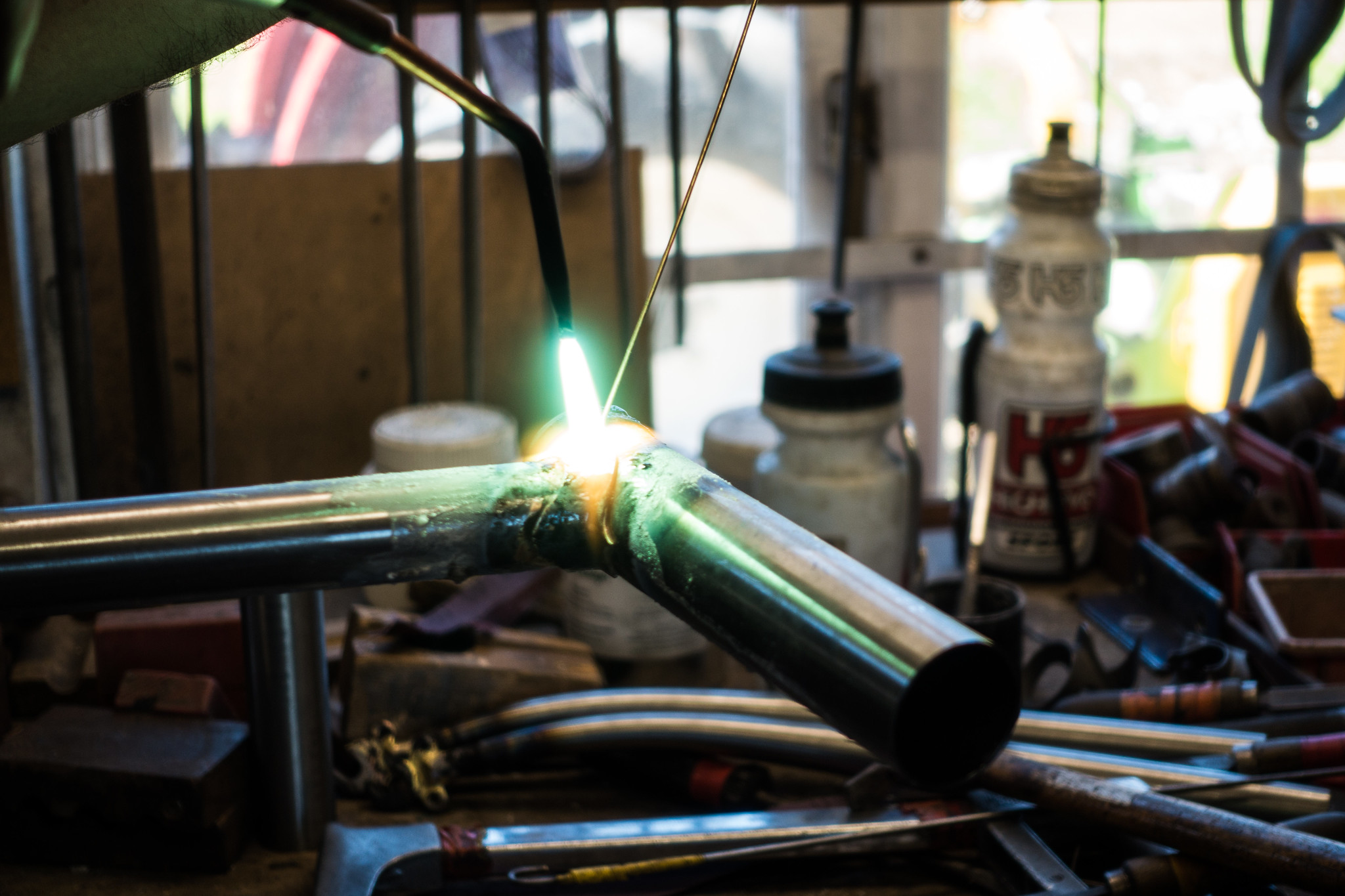

Back in the workshop, our first job was to trim some bits off our bottom bracket joint, and then braze the down-tube into the bracket.

Brazing requires a flux and a filler metal. In our case, we pasted the various parts with flux, and then were going to use thin brass rods as our filler material. The flux prevents oxidisation, while the filler, which has a lower melting point than the steel, bonds the steel together. The process involves heating the steel to temperature and then melting the brass into the gap, using the torch to draw the brass through, making a good join that is strong.

I’d never done anything like this, but under Dave’s tutelage I had soon brazed my first bits of metal.

Next up were the rear drop outs to the two chain stays. This involved first reshaping the Reynolds steel, before using a hacksaw to cut out a couple of indentations where the pre-made dropouts would sit. Lots of filing ensued when I repeatedly cut too small a hole for the dropouts.

Again, brass was used to braze the pieces together, followed by lots of filing to make the joins good and the visually smooth things out.

Over on the other workbench my fellow course mate David, who was building a slightly different type of bike to me using lugs, was starting on his front fork. I was going to be fillet brazing my bike – a touring bike – which is harder, but looks nicer. Nothing like setting myself a challenge!

Next up for me was doing the geometry of my bike. There are endless geometries available, and a lot of voodoo science too. I left myself in Dave’s hands, since he’s built thousands of frames over the years, and we soon had something that should work. Things that had to be taken into account were the relatively relaxed position on a touring bike and the fact that I have big feet and so need to think about making sure my heels stay clear of the rear panniers.

Geometry worked out, and it was time to cut my head tube using Dave’s lathe. He showed us how it worked, and then I performed the cut myself. It makes a perfect 90-degree angle that is razor sharp if you’re not careful.

And that was day one complete. On the way back to my B&B, I stopped off once again to watch he Lancaster continuing to perform for onlookers. Against the blue sky of an English summer, it was perfect.

Day Two

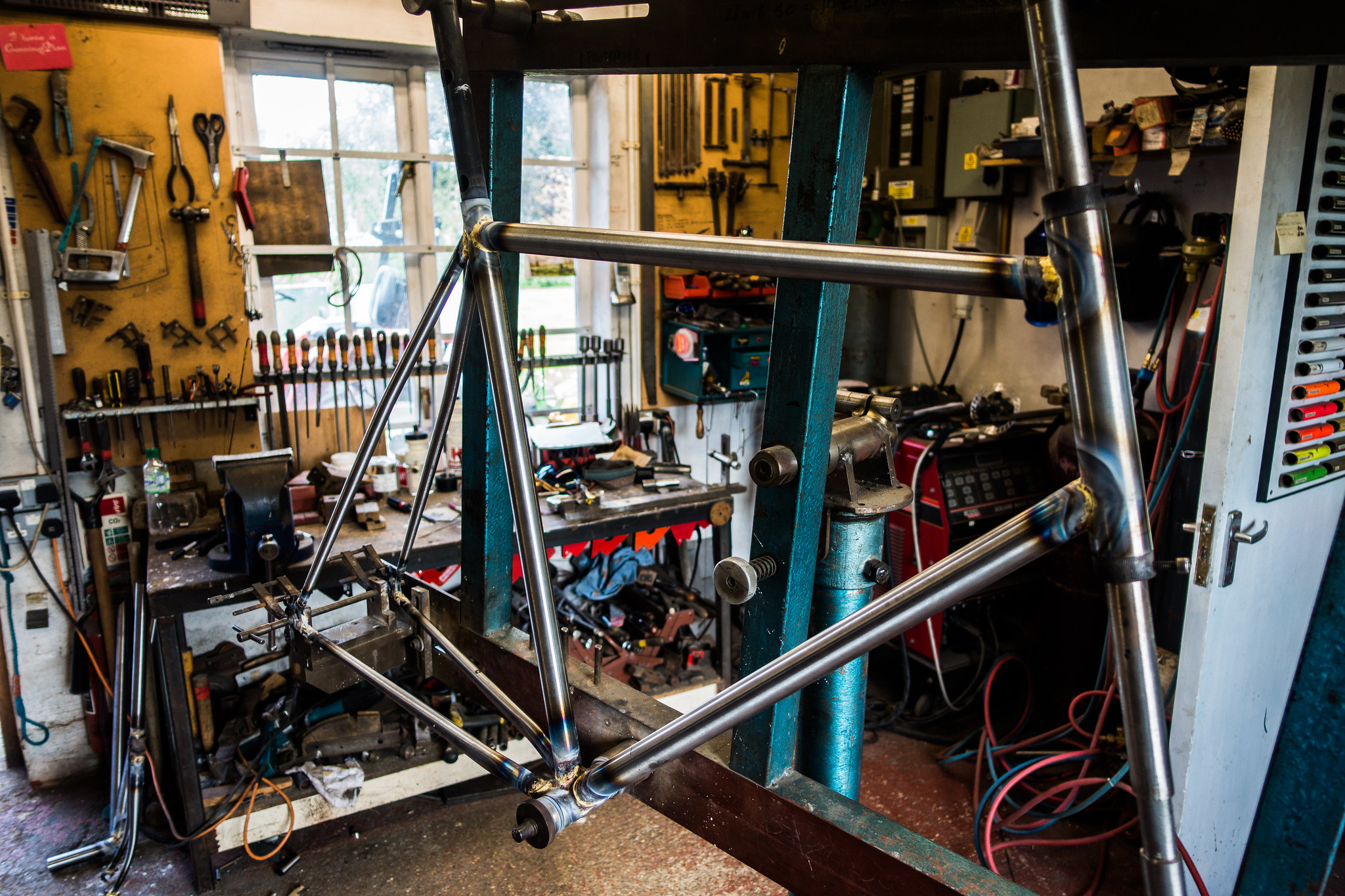

Today was a day of lots of filing, cutting, and yes, brazing. My bike was beginning to be assembled in Dave’s self-designed and built jig. Because I was building a fillet brazed frame, it meant that there were a great deal of angles to work out.

Dave’s a big believer in dispelling some of the frame building myths that perpetuate. Some things are more important than others, and there are a variety of ways of getting to a desired outcome.

With my bike, this would mean having a fairly flat top-tube, which is fine by me, while everything from my preferred crank length to the kinds of wheels and whether I’d be using disc brakes would be taken into account (Dave’s not a massive fan of disc brakes – but in any case, I would be using cantilever brakes on this bike).

Building the body of the frame means accurately cutting the various tubes to length – normally a bit long, and then filing back to make a perfect angle with the existing tubes. This is quite a fiddly process and means lots of filing, checking, going back and filing again ad nauseum. The concern is always that the more you file to get a fit, the less tube you have to play with. It’s a bit like the junior hairdresser taking a bit off the left, then a bit off the right to even up, but then a bit more off the left, and so on. A belt sander in Dave’s expert hands allows you to finish off a little and get as close a match as you can – somewhere around 0.5mm.

By far the hardest part was getting the seat stays right. The angles here are odd, and when, finally you’ve got one right, getting the other right, and then both matching means a lot of filing and fettling.

Finally, there was a bike-shaped-object in the jig, and the next job was to tack the various parts together. This is effectively making joints to the frame to give it stiffness, but ahead of the final fillet-brazing itself.

In fact, even the tacks give an enormous amount of strength to the frame, with Dave reckoning you could ride the back like that (it wouldn’t be recommended). The joints let the brass run all the way through after all. But by the end of the day, I had a tacked frame looking suitably familiar to me, and ready to go.

My fellow student, David, was building a lugged frame – which worked out well for the course. Because while I was using the jig, he was building his forks and was some of the sub-assemblies he would need. This way our work dove-tailed and we’d not both be using the same tools at the same time.

Today we had fewer aircraft distractions, although there was the odd Lancaster flight overhead and when I cycled back to my B&B, I had to stop at the red traffic lights that indicated something was coming in – in this instance a Typhoon, passing perhaps 10m above the road as it hit the runway just beyond (the very low) fence.

Day Three

Today was to be a day of fillet brazing. In essence, this would mean adding a smooth layer of brass on top of the joins I’d already made. The frame came out the jig very easily, and it could now be attached in a vice to allow me to work at the fillet brazing. David now needed the jig to assemble his bike, with a little work required to get the geometry right.

Each pair of tubes brazed had to be done in four sessions, with roughly a quarter of the way around the tubes brazed, stopping each time to file off the warm brass to get a good smooth braze. Seemingly Gary Fisher had let on to Dave how much easier it is to file when brass is still hot.

Even then, this means a lot of elbow grease since you’re trying to get a smooth finish.

The actual brazing itself involves getting the metal just up to the right temperature that means that brass – which comes in thin wires – to melt as though it was solder. You then want to use a combination of gravity and heat applied in the right place, to get the brass to form an even appearance. For a total beginner like me, this meant a certain amount of trial and error.

You also need a steady hand, something I sometimes struggled with when holding a flaming torch in one hand that is burning at 800C, while holding a stick of brass in the other – which all the time, was getting shorter.

The brass needs to be even with no bubbles or inlets. The joints need to solid and therefore strong. Dave watched carefully as I carried out this task.

By the end of the day, nearly all the brazing had been done, with only the rear dropouts needing a final bit of work. Running over the fillet brazes with a belt-sander gave the frame a final smooth appearance.

All of this work will be lost under the paint when it goes on of course, but it does make the lines very attractive, and much prettier than much of TIG welding you see in mass-produced frames.

Finally, a little ahead of schedule, I started work on my forks. I was warned when I started the course that choosing to use fillet brazing might not leave time to build forks, but it looked like I was going to have time to build them after all. I’d seen David build his, and a certain amount of the following day would be spent making them.

Otherwise it’s all the various cable guides, lugs and other appendages that still need adding, as well as reaming the head tube, and bottom bracket. The frame should indeed be complete by Friday lunchtime when the course finished.

We had additional distractions in the form of more Lancaster, Spitfire and Hurricane practicing. The various manoeuvres lead them to flying low right over Dave’s workshop. Invariably, as we heard the thrum of the engines, we’d drop what we were doing and rush out to see the planes pass overhead.

Day Four

Returning to the workshop, it was beginning to feel that I was into the home stretch. The first task for me was to make my forks.

I’d already begun filing – I was doing so much filing this week – and needed to get a good fit for the dropouts in the two fork stays. Once this was done, it was time to braze them into position. Clearly the pair had to be identical to get a nice symmetrical fork.

Dave gave us a steel cast crown into which the head tube and the two fork stays would be brazed. First I brazed the head tube into the fork, letting it cool and then filing it back to ensure a flat smooth underside to the fork. I’d managed to let far too much brass run through, and that needed removing.

Then it was the turn of the two fork stays, first cutting them to length – something I was pleased to do almost completely correctly first time of asking, with only a small amount of corrective filing required. Maybe I was finally getting just about OK at this filing lark.

My only memory of my solitary term of school metalwork was of endless filing of a bottle-opener that took weeks to make. I’m not even sure I ever finished the damned thing.

Finally, the fork stays were all brazed, and the only final job was to use the lathe to cut a 30mm diameter ring around the top of the tube. This left me only with the need to ream a screw fit in the top of the fork to serve as a mudguard mount and allow other attachments to be placed on the bike.

Then it was back to the main frame, where I now mostly needed to simply add the various braze-on lugs that do things like guide the gear and brake cables. Also affixed were the screws that allow for fixing pannier mounts to the front fork and the rear of the bike. Instead of brass, we’d be using silver solder to make many of these mounts. This requires a lower temperature, and an awareness that it’s a much more expensive material to use.

Invariably throughout this process, Dave had a series of specially built little tools that helped make these tasks somewhat easier. Occasionally I needed to line something up by eye, but more often than not, there was an aid.

Some of these needed building up, including making a bridge to run between the two seat-stays.

I finished the day with a good number of the braze-ons completed, and just a final few, including the attachments for calliper brakes to go.

David had got to a very similar point with his bike, and was in the process of affixing a number of braze-ons himself. His particular needs for his 650mm wheels meant a different pattern to my more “normal” frame.

I wish I could say that I’d improved leaps and bounds in my brazing ability over the four days so far, but I know that I’d need to do a lot more to get good at it. From lighting the oxy-acetylene torch to getting its heat right and not introducing too much heat to the wrong part of the bike, I’m still a rank amateur. I was still getting slight shakes when introducing brass or silver to the joint I was fixing. Fortunately, Dave was never far away to put me right.

Day Five

The final day of the course, and the majority of my jobs were to complete the various braze-ons about my frame.

Overnight, Dave had shot-blasted the two frames and forks, removing the heat marks and generally cleaning the frames up. He’d also used the belt sander to clean up some of the joints. To some extent, we were going to be undoing some of that work since we still had a few places where work was needed.

For me this was a fairly relaxed morning, since I easily had enough time to file, sand and braze the parts I needed.

However, I’m sorry to report that despite having had four previous days of brazing, I still hadn’t quite got the hang of it. Even getting the oxy-acetyline torch lit was a bit hairy – I suspect a consequence of never having owned a gas cooker.

The other major job I had was to put in a couple of support bridges. You never think of these when you make a frame, but they add structure to the rear dropouts. And of course, joining an oval to another oval, at an angle, meant more cutting, filing, checking, filing, checking and filing, until you realise that if you file any more away, the bridge will be too short and you’ll have to start over.

It did seem that my filing had now improved enough that I was actually removing metal when I did it – just sometimes too much metal.

The final thing I had to do was close up part of the seat stay, and my bike frame was complete!

Well – complete in that it would still take a little more cleaning and tidying on Dave’s part. But I could have carried that bike away and it would have been fine. Although as Dave pointed out, it would have rusted pretty quickly had I not painted and cleaned it.

There was still the small matter of painting.

Despite thinking about this bike for nearly a year, I didn’t have any real idea of what colour I wanted it. For ease, I’d decided to let Dave paint it, and he had a nice colour chart of short pieces of tubing in each of the colours he offered.

Beyond that, he could mask parts of the frame, blend colours and so on.

I’d spent the previous evening flicking through a couple of cycle magazines and browsing the internet seeking inspiration.

To be fair, my colleague on the course was not much better – to the point that he was going to leave the frame with Dave, but get back to him on his final choice of colour scheme!

But I ended up going with cobalt blue. The fashion in bikes these days is actually matt finishes, but Dave didn’t offer that, and in any case I wanted something classic. Not quite a royal blue or a racing green, but something that would stand out. A metallic coat.

Dave said he’d paint the frame the following week, and I made plans to pick it up a week or two after that. A week of drinking tea, and bike-building, all to the soothing tones of Classic FM in the background had come to an end.

In the meantime, I was getting more and more distracted by what was happening in the air above us.

Today was “Family Day” at RAF Coningsby. I knew this because every B&B for miles around was full up, and it’s an event that only takes place every couple of years. Friends and family come and visit the base, and most importantly, a major air display is put on for everyone.

First up were the Lancaster, Spitfire and Hurricane – who also managed to fly in formation with a Typhoon, the latter struggling to stay slow enough to match the speed of the other planes that were no doubt maxing out their engines.

Then we had a Belgian pilot flying an F16 and performing a very impressive display all around us. A pair of helicopters were less impressive – mostly because we couldn’t see what they were doing.

At the end of the course, we took final photos, said our goodbyes, and I headed to a field that Dave had directed me to where I might be able to see more of the display. Although there’s a particular spot at the end of the runway at Coningsby for aircraft spotters, when I’d passed it that morning at 8.30am, it had already been full.

This other field was somewhat more hidden, and seemed to only be known to a few spotters who were there with deckchairs and scanners, along with enormous 500-600mm lenses for their cameras.

Again, my small point and shoot wasn’t going to be much use, but I hung around for various displays of biplanes and wildcats, before the display I was really waiting for. The Typhoon display.

The Typhoon basically takes off vertically, soaring into the air like a rocket. It can perform remarkably tight turns, causing us spectators to twist around endlessly. It can also fly very quietly – seeming to almost glide at times – using its air brakes. A wonderful display.

There was more to come, but for me it was time to head home.

Now I had to wait for my finished frame, but had to start planning how the bike was going to be built up.

Later

Early one Saturday morning a couple of weeks later, I set off from nearby Norfolk to drive over to Dave’s workshop to collect my bike. I arrived a little early but the gate was open and inside the workshop my frame was now a blue cobalt colour and was being worked on by Dave. He was just reaming a couple of dropouts after the painting, and was putting in a couple of gear guides and a seat tube bolt.

A few minutes later and the frame was complete. We took it outside to examine it in the sunshine, where the light bounced off the metallic blue finish. The colour worked and I had what was undoubtedly a finished frame.

I carefully loaded the frame and its matching fork into the car, using a few blankets to ensure that nothing got scratched. This frame was going to get some true TLC.

I thanked Dave once more, and headed off with my prize. Later I would carefully wrap the frame in bubble-wrap since I had to travel onwards from Norfolk to my home via public transport, and I was scared stupid of getting it scratched.

Now it was time to build the bike up.

While it’s possible to build a frame, there are relatively few components that most people will build themselves afterwards. Perhaps the key one is wheels, and while I’d previously bought a wheel truing stand, I was worried about my abilities – or lack of them – in this field.

David, who had been on the course with me, had built a pair of his own wheels for his bike, and claimed that it was actually pretty straightforward. He’d recommended a book to buy – The Bicycle Wheel by Jobst Brandt. I’d found a copy online and ordered it. But I was still a bit uncertain. If my wheels went while I was on my bike it could be catastrophic.

I felt that wheel-building was something to aspire to, but not something I was quite ready for just yet.

But a hand built bike did deserve some hand built wheels. There are plenty of wheel builders around, and a colleague recommended DCR Wheels based in Lewes. I dropped David a line (everyone in this piece seems to be called Dave or David), telling him what I wanted, and he suggested a specification for me, using his own hubs and some Velocity Chukkar rims. These wouldn’t be cheap, and it’d take three weeks build time since there was a queue of wheels that he was working on. Nonetheless, I ordered them.

I created a spreadsheet filled with all the rest of the components I’d need. Years earlier, I’d also read Robert Penn’s book, It’s All About the Bike, where he’d essentially built – or had built – the finest bike he could, visiting wheel builders in the US, and the Campagnolo factory in Italy.

I was on a bit of a tighter budget, and decided I’d stick with what I knew. So, that meant largely Shimano components, and mostly Ultegra. While I did toy with the idea of a triple chain ring, to allow me to get up hills with a fully loaded bike, that would mean mountain bike gears, and they don’t work easily with road shifters. This bike was going to have drop handlebars, and so it really needed a road specification gearset.

So it would have a compact Ultegra chainset, and an 11-32T cassette at the rear, allied with front and rear Ultegra derailleurs. The bottom bracket would also be an Ultegra one, while the brakes would be Shimano’s cantilever model Ultegras. These are mostly designed for cyclocross bikes, but they make sense for a touring bike. Dave Yates had actually suggested Tektro cantis, but I was worried about marrying the pull of an Ultegra shifter with Tektro brakes. Going all Ultegra seemed the safer bet.

I wasn’t at all sure about what handlebars I wanted, but I settled on Nitto Noodle bars. These are actually silver, and while bars of old always used to be silver, I hadn’t completely clocked that every bar these days tends to be black. And that means both stems and headsets are largely black.

Even though it would have bartape, a silver bar with a black stem didn’t work for me aesthetically, so I found a silver stem to match.

Headsets are, like bottom brackets, an area I get thoroughly confused about. There are a myriad of types and manufacturers seem to make dozens of variants. Which did I need?

Well I knew I needed a threadless headset, and I’d quite like it to be silver. That limited my options severely, with only high-end manufacturers like Chris King meeting those needs. But I found an M:Part model at a more reasonable price.

Fitting the headset was another concern, and I knew I’d need to either buy, build or borrow some tools to fit both race crown on the fork, and firmly affix the top and bottom cups to my frame.

The saddle was a relatively easy choice – a Brooks 17. I’d recently fitted one to my Brompton and felt it’d work well on this classic bike. This would be attached to a silver Deda aluminium seatpost. The saddle would be black and therefore my bartape also black. I really like Canyon’s own Ergospeed Gel tape that came on my Inflite AL8.0, so I ordered some of that from them.

For the tyres I decided on some 32mm Schwalbe Marathon Supremes that seemed to have good reviews, and I also ordered some SKS Chromoplastic Mudguards.

Pedals would be a pair of Shimano A530 flat/SPDs. These allow you to ride either with or without cycling shoes.

I already had a Tubus Logo rack which would be transferred to the bike in due course, and aside from some lights, a seatpack and a pair of bottle cages, that was the full bike specification.

I placed several orders with a variety of retailers, and waited for boxes to arrive…

My original plan had been to purchase everything, and then embark on the build. I did indeed accumulate a big pile of boxes of parts, with items from a number of different retailers. But key to all of these was going to be the wheels, and I was in a queue to get my wheels built. It’s perhaps not surprising that the summer months are the busiest for wheel builders.

The problem was that much of what you do with a bike depends on the wheels. Sure, I could drop in a temporary set of wheels and build around those, but that felt wrong.

Nonetheless, I could do a couple of jobs. First off was treating the inside of the frame to prevent rust. Dave had said to use Waxoyl, widely available at Halfords. There are bikeframe specific treatments, but they’re not cheap. I went out and bought a can of clear Waxoyl, and taking my bike outside, attempted to spray the inside of the steel tubes.

The first thing to note about Waxoyl is that it comes out as something of a goo. Although delivered via a spray can (there’s also a version that is applied via a paintbrush), it does accumulate very easily. And looking online showed that in heat, excess liquid came out as a yellow residue. So I also used some GT85 spray to drive out the excess as best I could. Of course, that may have also removed some of the Waxoyl. Hopefully, between the two substances, I had at least created a rust barrier.

The first component I added to the bike was the bottom bracket. Now I must confess that I find the whole area of bottom brackets immensely confusing. There are lots of different types, and designs, as well as screw fittings and everything. It’s one of those areas of the bike, I’ve left to the professionals in the past.

But in truth, the Ultegra level bottom bracket I fitted to my bike was pretty straightforward. I bought a cheap tool, although had to use the plastic adapter that came with the bottom bracket itself. Then it was just a question of using some lithium grease and screwing it into place. I confess that I don’t have a torque wrench to get the exact tightness right, but using the weight of my body, I got it in as far as it would go.

Then it was the headset, another area I wasn’t too sure about. First off, I had to fit the crown race to my fork. The internet will furnish you with many DIY solutions involving washers and lengths of PVC tubing. But I’d bought a proper tool for the job. Except, I had a problem. The length of my fork – yet to be properly cut to length, was so long, that the crown race tool wouldn’t reach. So I first had to cut off a conservative length of the fork to allow me to even fit the crown race!

The fitting was simple, and just involved holding the fork with the tool in my left hand and hitting it with a hammer in my right hand. The key thing here is not to rest the fork down. I didn’t want to damage the dropouts.

Next it was going to be fitting the cups onto my head tube. These cups are part of the headset assembly, and need to be applied with a certain amount of pressure. The fit is tight!

Again there are DIY tools to do this job, and again I’d bought something to do the trick. But I had a problem. My head tube is quite large, and I’d discovered that the tool was designed for smaller ones.

Eventually I worked out that if I fitted one cup at a time, and unscrewed the tool as far as was safe to do so, I could just fit the tool around my head tube. I had to use an adjustable spanner as part of my solution, but I managed to fit both cups properly into place.

The rest of the headset really required a wheel and inflated tyre in place to make sure I got the height of the fork right. But that went back to my wheels again. And so, the frame was put aside until I had more components.

The final arrival for the big bike build was a package containing my two new wheels from DCR Wheels.

I finally felt able to start the build. I’d carefully accumulated every single component necessary to build a bike. Indeed, it turned out that I had a few “spares.” Shimano, it turns out, packs some brake and gear cables with its shifters, so my separate cable packages were unnecessary.

But it also turned out I didn’t quite have what I needed in a couple of places. The first place I fell foul was with the headset. It turns out that cutting my fork down to size was more fiddly than I’d anticipated – at least without a tool to ensure I cut a perfectly straight line. It took a certain amount of filing down to get a decent finish to my steerer.

But that wasn’t the real problem. That was getting the star nut to adhere to the side of the tube. I had a 1 1/8″ tube, but it seems that not all 1 1/8″ tubes are the same. I actually had two sets of star nuts, and having finally worked out how star nuts should ensure a snug fit, I realised that my steel tube was slightly wider than some, and the star nuts were slipping down. I nipped out to the only local bike shop to me – a Halfords – thinking perhaps I’d damaged the two sets of star nuts I had. But this wasn’t the case. The new one was also too small.

I ordered a Hope Head Doctor from Evans and figured that this would solve my problem, being expandable to fill the tube.

Meanwhile I’d opened by cantilever brakes package and realised I had another problem. The front brake cable needed to drop vertically down to the centre of the cantilever to work properly. At least if I wanted a decent pull that wasn’t off centre.

The back of the bike was fine, since there was a central slot for the cable to reach, and a barrel adjuster in place. But there was no such thing at the front.

You can get pieces that slot into your headset, but these would be no good for me, since my head tube is quite long.

Searching around on Google, I found an image of a cyclocross bike with the same CX70 brakes I was using. This bike had a front fork hanger than guided the cable down. Again, this was going to be a special order, and I would need that part before I fitted the front brake.

But that weekend saw the tyres, wheels, cassette, front mech and rear mech all fitted. My long chainstays meant I needed nearly all the links of the chain I fitted.

I managed to get the front mech shifting properly, but the rear mech was giving me problems. I only seemed to have 9 of the 11 gears, and no matter what I did, I couldn’t get any more. One for another day I decided.

My frame is quite large, and as a consequence, I didn’t need much seat post showing.

At the end of a busy weekend, I had a bike still missing its front brake, bottle cages, handlebar tape, and properly tightened headset. There were also mudguards and a rack to go on. I’d got rid of a lot of boxes, and had a bike that now looks like a bike.

It was getting close!

I ordered a few more bits and pieces. Top of the list was a front mech cable hanger. Tektra make one that uses the mount on the front fork to let the front brake cable drop into place vertically above the cantilever brake.

But on fitting the piece, I found I had another problem. There was now not enough room for sufficient cable pull to engage the brakes. The angles meant that the top of the cantilever hit the head of my cable hanger.

No matter how I aligned the brakes I couldn’t avoid this. In the end, my solution was to find a shorter link wire – the contraption that delivers pull between both sides of the cantilever. I found a couple of shorter sizes on eBay and one of them seemed to work. I now had a working front brake.

In the meantime, I also fitted some mudguards – my hacksaw coming in useful in making sure that the stays were the right length. I did discover at this point that a mounting hole on my bike was in the wrong position at the front, and I had to make some “manual adjustments” to get it fit OK.

I also finally put on some bar tape, and now had a broadly functioning bike. The first test revealed that the position was indeed more upright than my existing bikes. But this is what I’d wanted. While the frame is large, and I perhaps could have had a downwards sloping top tube to allow more seatpost to show, the bike is wonderfully well fitted to me.

There was still the issue of the headset though, and my gears weren’t right. These would both require shop assistance. The worry at the back of my head was that there wasn’t much room for manoeuvre if the top of the fork needed some remedial flattening. I had a single 3mm spacer in my stack and no more.

Either way, it was time to go to a bike shop, and so one morning, I set off to work very early and to an early opening bike shop near work, to get the final snafus sorted out.

That afternoon, the shop had fixed everything perfectly and I now had a complete, and fully functional bike. I rode it home that evening with delight!